May Day (May 1) may have enjoyed longstanding significance as a day honoring the struggle waged by working men and women the world over, but Oshkosh conservatives were intent on reconstituting May Day 1970 as "Law Day, USA." While attorneys fanned out throughout the city giving speeches on the Law Day theme, "Law-Bridge to Justice," local schoolchildren bedecked in red-white-and-blue attire viewed films addressing the importance of maintaining "law and order" in modern American society.

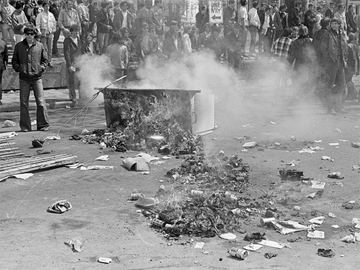

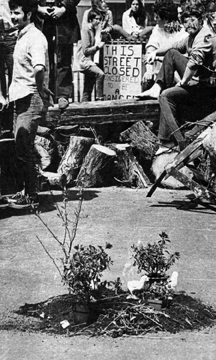

The events of "Law Day, USA" might have received greater attention in area newspapers had not a group of thirty students stationed on Algoma Boulevard begun to hand out leaflets at 10 a.m. proclaiming "the traffic problem" on the busy thoroughfare "is now reaching tragic proportions and some type of student action is needed now to protect student well-being." Before long, a growing throng of students (estimated at 400) began assembling in the street and commenced on closing the street off from local traffic. Constructing barricades from logs, concrete bumpers and large trash containers, students renamed Algoma "Free Boulevard."

Although a few local residents acknowledged the traffic problem and sympathized with students, most Oshkosh citizens were appalled by the students' actions. "I wish I was driving a semi," one irate driver told a Paper of Central Wisconsin reporter, "I'd break this up in a hurry." Another driver clutched an imaginary machine gun, aimed at the student protestors and began firing fanciful rounds of ammunition. "One is horrified at the appearance, clothing and hair of this wild-looking bunch," said another Oshkosh resident. "It makes we wonder…why the taxpayers of the State of Wisconsin should waste tax dollars underwriting their education." Likewise, a letter to the editor of The Paper, signed by "Sick of paying taxes," asked: "Are the people who live here all the time supposed to fight the traffic all the time, so the 'poor dear students' do not have to even turn their heads when crossing the street?"

The Paper of Central Wisconsin, May 2, 1970.

The Earth Day teach-in several weeks earlier had temporarily raised hopes on campus and within the community that student radicals had found an issue to which they might devote their energies. Rather than lure students into further antiwar protests, many hoped Earth Day environmental activism would steer activists in a positive direction and foster the recognition of mutual concerns with local citizens. But the Algoma Street protest of May 1, 1970 quickly extinguished those hopes. Not since the fallout from Black Thursday had relations between Oshkosh and the university grown so strained. What happened? Why did the events of May 1, 1970 play out the way they did?

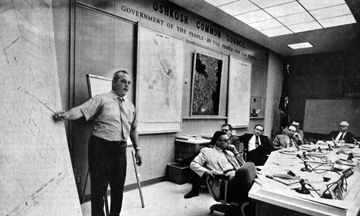

On the night of May 4, 250 students crowded into an Oshkosh Common Council meeting called to address the Algoma Boulevard issue. After sitting through ninety minutes of equivocation, dissembling and promises of (more) future study, a freshman WSU-O student from Evanston, Illinois burst out: "You've lied to us, you've beat around the bush. Well, damn it, it's too late. I'm going out into the streets [to demonstrate] and so is everybody else here." For this student and the roughly one thousand students who streamed out onto Algoma Boulevard, the Oshkosh Common Council became a proxy for President Nixon and the National Guard troops who fired on Kent State students earlier in the day.

The Paper of Central Wisconsin, May 2, 1970.

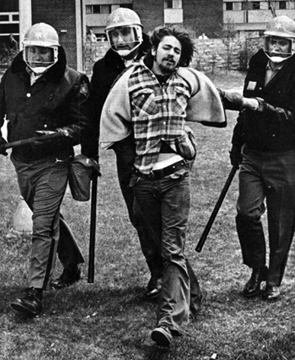

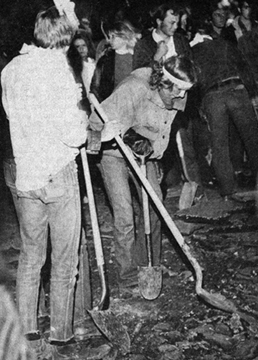

At 11 p.m. students once again barricaded Algoma, set tires and garbage on fire, and, using the shovels and pickaxes that Oshkosh residents loaned to students earlier when they constructed Shapiro Park, began digging up a thirty-foot section of the road. The intervention of Winnebago County police, backed by personnel from fifteen police agencies throughout northeast Wisconsin and outfitted with riot gear, forced the students to retreat.

May 4. The Paper of Central Wisconsin, May 5, 1970.

Students pelt police with rocks outside of Gruenhagen Hall.

The Paper of Central Wisconsin, May 6, 1970.

To begin, we need to recognize that the issue of Algoma traffic had mattered greatly to students for some time. Ever since WSU-O had engaged in its remarkable period of growth in the mid-1960s, students had complained that local residents heeded little concern for their safety when they attempted to cross Algoma on their way to and from classes. To some students, particularly the young men who wore their hair long in 1969 and 1970, it seemed that locals driving vehicles on Algoma intentionally sped up when pedestrians attempted to cross. In the spring of 1969, student picketers brought the issue to the attention of campus administrators and the Oshkosh City Council and in return were given a flashing yellow caution light near a popular campus crossing point and vague assurances that the issue of Algoma traffic would be studied in the future. Although WSU-O officials (with the help of findings issued by a Chicago-based consulting firm) proposed diverting traffic around campus, the Oshkosh City Council and City Manager Angus Crawford stood steadfastly on the side of motorists who wished Algoma to remain open and unobstructed.

The Paper of Central Wisconsin, May 6, 1970.

An equally important precipitate of student action on May 1 was President Richard Nixon's April 30 announcement that the United States had invaded Cambodia, a hitherto neutral neighboring country to Vietnam. On campuses throughout the United States, students reacted to this apparent escalation of the war with rage. President Nixon had earlier told the nation that he was determined to wind down the war, but the Cambodian invasion seemed to prove the exact opposite. The credibility gap, initiated by Nixon's predecessor, Lyndon Johnson, was suddenly growing wider. Early on the morning of May 5, several hundred police personnel kept students at bay while large V plows and equipment from the Winnebago County Highway Department advanced to the barricades to clear, repair and reopen Algoma Boulevard. While a Department of Natural Resources airplane flew overhead looking for student rooftop snipers, some irate students lobbed rocks and chunks of concrete at police. Outnumbered by the estimated 2,500 students, the police wisely decided not advance aggressively. As they continued making arrests for unlawful assembly and disorderly conduct, students issued hoarse-voiced reminders of the fate that befell the four students killed at Kent State. "This is it….That's why we're here…the war," yelled one student. "It was the road until yesterday…Now it's what happened at Kent State." The installation of 15-mile-per-hour speed limit signs the next day might have been seen as progress by some students, but many more undoubtedly agreed with the student body president when he declared Algoma Street "a dead issue." The students' recent venting of rage "was Cambodia," he declared, "not the street."

The Paper of Central Wisconsin, May 8, 1970.